In my youth, I once attended a session on Sufi stories. One story from that evening has remained with me for many years. It carries within it a seed of wisdom so subtle that each time I retell it, something deep within me responds viscerally—sharpening my clarity about the significance of self-remembrance in spiritual practice. With every retelling, the lesson becomes deeper and more nuanced.

The story revolves around a chieftain and his three sons. In those days, it was customary for a chieftain to bid farewell to all his loved ones before embarking on a journey, for both travel and life were uncertain. On one such journey, the chief does not return. Each day, the youngest son asks, “Where is my father, and when will he return?” After a year of his daily remembrance, the two elder brothers decide to venture into the forest in search of their father.

Deep in the forest, they discover a skeleton they recognize as his. Since both brothers are shamans, they use their powers to revive him: the eldest reconstructs the body, and the second breathes life into it. The joyous trio returns to their village, where the clan greets them with celebration. After the festivities, everyone wants to hear whom the chieftain will name as his heir. The eldest expects to be chosen for recreating the body; the second believes he deserves the honour for restoring life. But the chieftain names the youngest as his heir, saying it was his daily remembrance that kept him alive.

This story reveals the profound importance of remembrance—the act of keeping the Self alive. Unless we consciously acknowledge, each day, the divine force that animates us, we drift into sleep and forget our aliveness.

Recently, during a meditation session, I heard an inner voice say: “The divine in you can remain alive only through remembrance of it.” It was the same message the Sufi story had impressed upon me, now echoing within my consciousness. How was I to respond to this inner call?

As I stayed with this nudge and contemplated its meaning, I became more aware of how frequently I fall asleep, how moments of self-remembering arise but vanish swiftly as my attention is seized by my habitual self. Yet, despite these lapses, I feel an inexplicable urge to persist—to see how this practice of being present might become more conscious and steady in daily life.

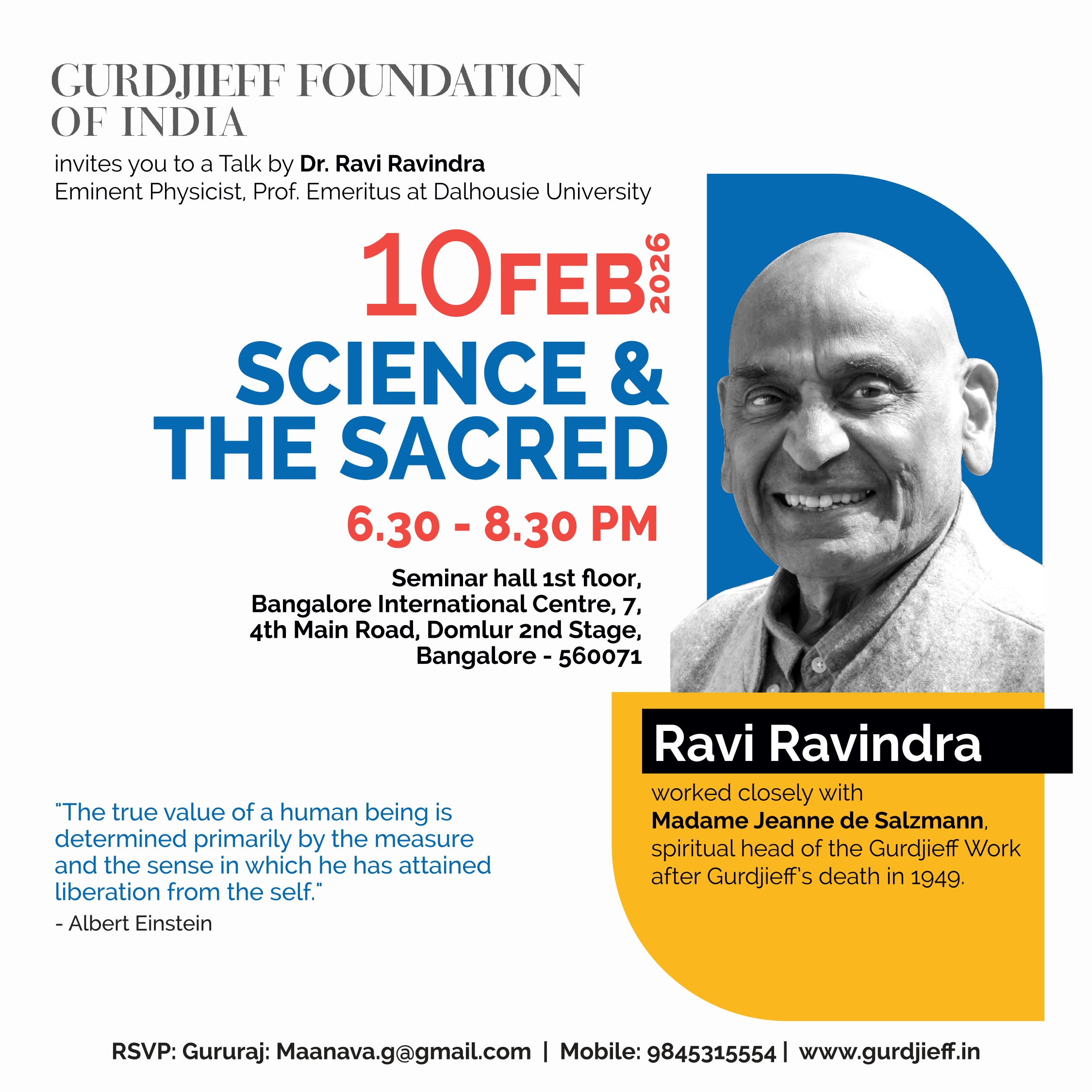

Theoretically, one may read what Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, Madame de Salzmann, and Ravi Ravindra have written about self-remembering. But its true value can only be discovered through one’s own moment-to-moment struggle. Even self-observation, I have found, is incomplete without self-remembering.

Before sharing my own struggles with presence and consciousness, I wish to recall the definitions of self-remembering that have most inspired my exploration.

Gurdjieff described self-remembering as a state of conscious attention in which a higher energy becomes available to the physical, emotional, and mental functions of a person. In this state, one “remembers” by being present to who one truly is—beyond the ordinary sense of identity. Conscious attention, for him, was not a function of the mind but a higher force that could direct thought, feeling, and movement toward harmony.

According to Gurdjieff, self-remembering is a condition in which one is aware of both oneself and one’s actions:

“Self-consciousness is the moment when a man is aware both of himself and of his machine. We have it in flashes, but only in flashes. There are moments when you become aware not only of what you are doing but also of yourself doing it. You see both the ‘I’ and the ‘here of I am here’—both the anger and the ‘I’ that is angry. Call this self-remembering, if you like. When you are fully and always aware of the ‘I’ and what it is doing, you become conscious of yourself.”

— Gurdjieff, Views from the Real World

Madame de Salzmann described self-remembering as a state of global consciousness, where one is simultaneously aware of both the part and its relation to the whole:

“Our effort must always be clear—to be present, that is, to begin to remember myself. With attention divided, I am present in two directions. My attention is engaged in two opposite directions, and I am at the center. This is the act of self-remembering… I wish to see and not forget that I belong to these two levels.”

— Jeanne de Salzmann, The Reality of Being

Ravi Ravindra views self-remembering as the effort to connect with the divine particle within us:

“As spiritual searchers we need to become freer and freer of the attachment to our own smallness… Recalling our own experiences in which we acted generously or compassionately, without expectation of gain, gives us confidence in the existence of a deeper goodness from which we may deviate.”

— Ravi Ravindra, The Wisdom of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

From these descriptions, it becomes clear that two forces coexist within us. While we must be aware of the ego-driven “me,” we must also remember and affirm the higher divine “me” within the same moment of presence. Only then can we truly perceive how the smaller “I”—the mechanical, reactive self—operates, and how connection with something higher infuses our being with aliveness.

When I joined the Gurdjieff group in India, we were given tasks designed to help us learn how to be present—crossing thresholds consciously, working with awareness, eating with attention, walking and listening with self-remembering. These tasks revealed how fleeting my capacity for presence truly was. I would forget quickly and be overtaken by habit. Yet, through these struggles, I began to experience flashes of seeing both my ordinary self and the divine presence within. Most of my actions were guided by my habitual mind and emotions, but occasionally something higher acted through me.

How, then, could I invite this instrument—myself—to be more vigilant before I thought, felt, or acted? How could my thinking, feeling, and doing become harmonized? At first, this effort led only to hindsight, remorse, even guilt. But as I persisted, something in me learned to witness my inner movements with detachment. Occasionally, my responses became more integrated and conscious.

Having tasted moments free of egoic control encouraged me to continue. Yet I also saw that even this striving could become ego-driven—a desire to achieve or attain. Gradually, I realized it was not about doing, but about seeing without interference. Madame de Salzmann’s words resonated deeply:

“The question is not what to do, but how to see. Seeing is the most important thing—the act of seeing… It is not the thoughts themselves that enslave me, but my attachment to them. Seeing does not come from thinking.”

My focus thus shifted from doing to being—to accepting what unfolds, becoming more receptive, inviting the divine to reveal itself through stillness, silence, meditation, awe, and wonder. I began to see that freedom does not come from rejecting the ego-self, but from understanding and accepting its place. In this coexistence, vigilance grows.

To nurture this vigilance, I continue to work with three ongoing practices:

- Seeing my inner disorder with compassion.

True seeing, I have found, is intrinsically compassionate. Judgment arises only when the mind interferes, seeking to categorize according to known patterns. When seeing is pure and beyond the mind, it becomes nourishing and accepting. The more I can see my fragmentation and accept it, the less it controls my actions. - Bringing gratitude into remembrance.

Though I have often avoided ritual, I now see how small rituals can aid Self-remembrance. Upon waking, before the world captures my attention, I invoke gratitude for the divine breath that sustains me and for the chance to live another day. This brief ritual transforms waking into a moment of awakening.Similarly, I attempt to bring gratitude to meals or moments of work, though hunger and distraction often intrude. When cooking for my family, however, the act itself becomes a form of loving awareness—a quiet space for self-remembrance. I also use car rides and walks in nature as opportunities to recall the divine within and around me.

- Preparing the instrument for higher connection.

Madame de Salzmann often asked: Where is your attention when you self-remember? Reflecting on this, I see that much of my attention is still consumed by ego-driven pursuits. Although I set aside time for meditation, sacred reading, and conscious work, my everyday activities often draw me outward. The realization has dawned that the focus must shift from doing to seeing—from activity to receptivity—so that my instrument may become more attuned to higher energies.

“In my usual state, my attention is of low quality… But this attention can be transformed. By turning it inward, the energy concentrates until it forms the center of gravity of my Presence.”

— Jeanne de Salzmann, Going Toward Consciousness

To Self-remember is to awaken; to awaken is to live.

Meena Kaushik 12th October 2025