Given the diversity of India, in terms of region, language, religion, food, clothes, lifestyle, there is a possibility of endless numbers of ‘us’ and ‘them’. This has been historically so but there have always been some unifying factors that have cut across some of these differences and brought people together. This crisscrossing of unity and diversity has held the nation together before and since Independence. It has been the warp and weft of our lives, the homespun that the charkha (the spinning wheel) stands for in the Indian identity.

Jawahar Lal Nehru, in Discovery of India, states, “The diversity of India is tremendous; it is obvious; it lies on the surface and anybody can see it. It concerns itself with physical appearances as well as with certain mental habits and traits…Some kind of a dream of unity has occupied the mind of India since the dawn of civilization. That unity was not conceived as something imposed from outside, a standardization of externals or even of beliefs. It was something deeper and, within its fold, the widest tolerance of belief and custom was practiced, and every variety acknowledged and even encouraged” (Nehru, 1946, 1993: 61, 62).

M.N. Srinivas (sociologist) felt that in India, Hinduism played a big role in providing the attitudinal framework for the tolerance of religious, ethnic and caste diversity. The ‘little tradition’ in Hinduism that related to rituals, mythologies and folk practices was imbibed across different religious and ethnic groups, rural and urban, stemming from the symbiotic relationships between these groups either through geographical or spatial proximity or economic interdependence. Culturally and religiously diverse groups in India have lived in harmony for ages borrowing each other’s rituals, food habits and lifestyles making ‘the other’ still a part of ‘us’.

Current anthropological research shows that the Indian identity is in a state of flux like never before. Multiple influences emanating from across the globe and from within India are creating tidal waves within what is considered ‘Indianness’. Some people are strongly rooted within their traditional values and customs. For them the multiplicity of external influences through modernity, global exposure to other cultures, and the new thinking within India is interesting, worth exploring and even adopting. They choose what they wish to follow and incorporate what they find is useful for their growth.

On the other hand, the data also shows that there is a section of the population, not linked to any particular class, that is deeply insecure and nervous about losing their Indian identity. Spread across caste, class and community, they are the most vulnerable populations and their angst is making them cling doggedly not only to the traditional mores they have been socialized into but also to seek out the mythical notion of India and its past glory to boost their uncertain sense of self.

If this endeavor remains within the boundaries of their individual search, the social implications may be contained. However, given the deep sense of insecurity they carry, they seek others like themselves as aides towards the creation of a community that shares a commonality of interest.

The other face of insecurity is arrogance. It represents the need to bolster oneself in the belief that what one holds to is right and there is a need to proselytize and to convince others that we are ‘different’ from them. Anthropology, history and psychology have long demonstrated the need for dumping the projections of one’s own negative traits onto the externalized ‘other’, the Kauravas of our lives.

Today, the insecurity engendered by an identity in flux, is creating safety through parochial silos which seek to have complete uniformity within and all diversity without. All forms of difference are ‘othered’. Animals, for instance have been ‘othered’ for centuries, viewed as objects and hunted, killed and eaten. Women have been ‘othered’ within both patriarchal and matriarchal social organizations, used as objects of exchange between lineages, controlled and dominated. In this context, it has long been known that nature, the source and mother of all, has been othered.

The lexicon of othering is filled with words like domination and conquest; its manifestations are the utter destruction of the planet that we see around us today. Destruction is the result of the way we perceive nature. We perceive nature not as divinity to be revered and worshipped but as resources to be exploited.

‘Othering’ creates the conditions for violence and the violation of the other. Violation is more possible when dealing with an ‘other’ than when one is dealing with those who are one’s own family, community or nation.

Where does othering end? Today, othering has created Hindus and those who are given to Hindutva, and it has ignited the flames of mistrust. Minorities and the majority use arrogance to bolster their frail beliefs. The ethos of ‘othering’ is spreading across all our relationships. ‘Othering’ is also dividing the frailty of age with the belligerence of youth.

In Mumbai, a friend’s driver was told by two young men on a motorbike, “Old man, watch out, we will take you out and burn you if you do not drive carefully”

In America, Brazil and other countries, racial tensions that are always simmering, have escalated as has the accompanying anguish.

Language, ethnicity, culinary and lifestyle differences…the list is endless. Once othering has permission, it can ignite the flames of hatred and violence. And that has no end.

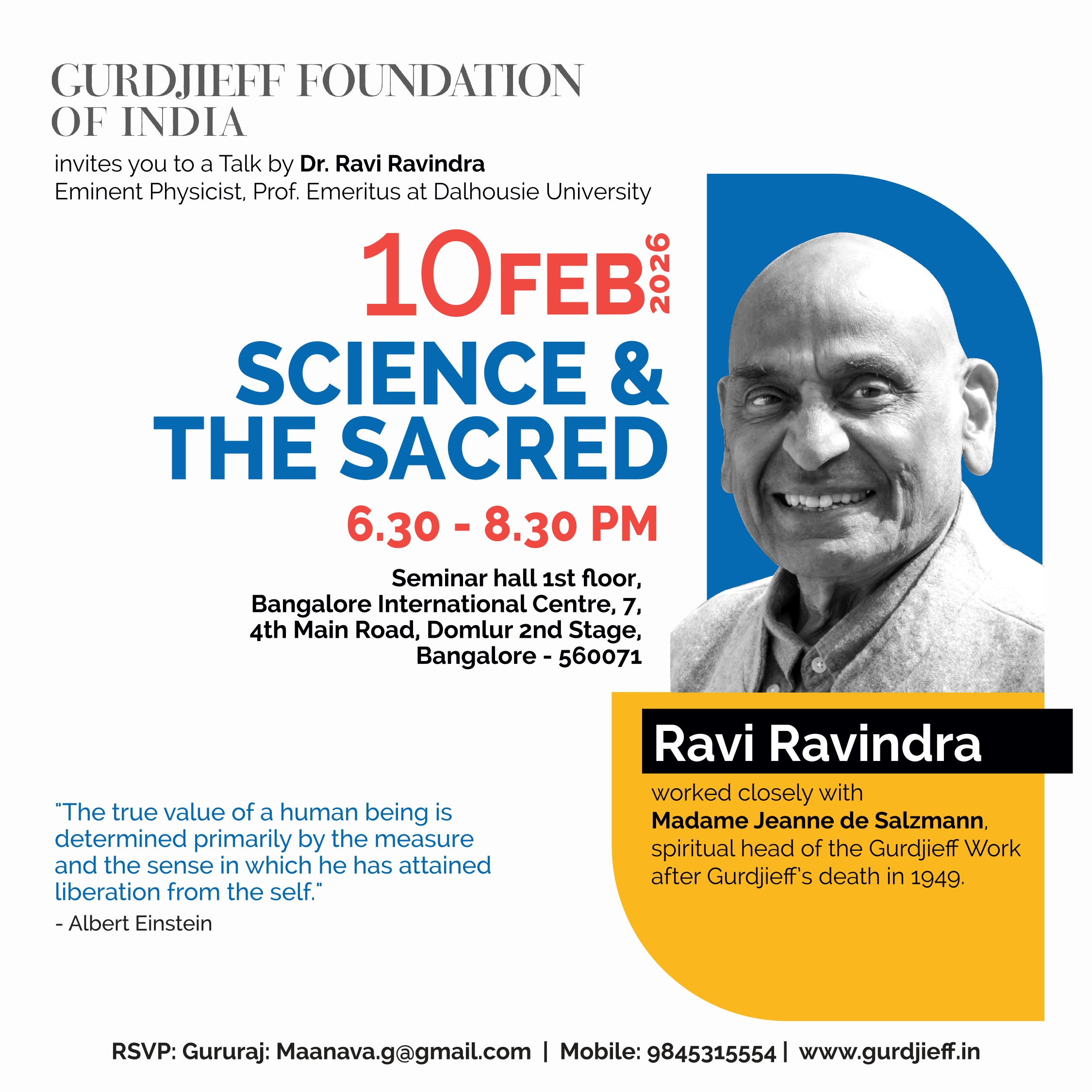

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna explains to Arjuna that “The gunas act upon the gunas” It is all a play of forces. “And the states of all beings – the harmonious (sattvic), the passionate (rajasic) and the inert (tamasic) are from Me alone. However, I am not in them, they are in Me. The whole world is deluded by these three kinds of becoming, composed of the gunas. And does not recognize Me, supreme beyond these and imperishable. My divine maya, composed of the gunas, is hard to surmount; only those who turn and come to Me cross beyond it.” (The Bhagavad Gita- Navigating the Battle of Life by Ravi Ravindra 2017 Page 129, Shloka 7.12-14)

This is the arena where owning and othering, self and other exist. Rajas, the force that initiates action and the dark inertia of Tamas, born of ignorance, is the quality that denies the affirmation of Rajas. These are the forces of action and reaction. The play between Rajas and Tamas is integral to the process of action and reaction, to the Kauravas and the Pandavas who are a part of us and who we are. I have a Duryodhana in me and I have Arjuna in me as well. The battle of Kurukshetra is my inheritance at birth. Whom do I choose to be?

The process can be endless were it not for the third guna which is also an integral aspect of the universe. This is sattva, the force of harmony, the force that reconciles the opposites. Sattva brings tamas and rajas into position by transcending both. Sattva is the ideal state that the entire Hindu tradition works to achieve through rigorous sadhana and austere tapas. Sattva is an affirmation of the Unity of Being, the subtle and pure quality of Oneness in the universe.

“O Bharata, sattva attaches one to happiness, rajas to action and tamas, by obscuring knowledge, to negligence. O Bharata, at one time sattva leads, having overpowered rajas and tamas; at another rajas, having overpowered sattva and tamas; and still another time tamas leads, having overpowered sattva and rajas. (Ravi Ravindra 2017, Page 202; Shloka14.9 -10)

But woe is us, caught on the wheel of the gunas, subject to forces we do not understand or have power over. We vent our hatred and anger on all those who are different from us.

However, there is a direction and a hope because the “‘svabhava, the essential inner being of a person, is adhyatma, the highest self, …in other words, Krishna.. ”, the higher levels of consciousness, the gods that all pray to, regardless of religious affiliations, reside in each one of us as our own svabhava or true nature. (Ravindra 2017 page 137) There is “an intimate resonance between our svabhava and Krishna’s own ‘madhbhava’” which sees the Kauravas and the Pandavas with an equal eye. To one he gives his army, to the other his wisdom.

The burning and practical question for all of us who care about the world we live in, is: Is it possible to end the process of ‘othering’ once it takes root within the fabric of a society? Are we not asked to urgently stop this rising tide of ‘othering’ which is fuel for violence? Are we not asked to see that non- violence needs to be understood as ‘non-violation’ of all the others with whom I have been given this world to share and cherish?

As we stand at the brink of an ocean of strife, a deep chasm of sorrow is being fed by hatred of the abstract ‘other’. As I see the waves of violence, lynching of young children in their teens and early twenties and thirties, of old people and of women, of tribals and Dalits, of black lives in America, and women in Brazil, the reaction in me drowns all the finer sentiments of ahimsa. I react with anger and disgust. I see that given the stimulus I too could become one of those whom I rail against. I too am trapped by the force of the rajas and tamas in me. I too enjoy the feeling of lashing out against the other as I feel superior in my righteous anger.

But my Hindu roots tell me that the Self in me is the Self in all of us. The Hindu tradition is based on a deep understanding and knowledge of the Unity of Being. Each Hindu is called to seek and to find the Self within because only the Self can see with an impartial eye. Only then can one be free of the process of ‘othering’. I have to stop ‘othering’ and violating the other because of my own insecurity. My righteous anger is only the other face of my insecurity.

As Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Christian we are manifestations of the one Atman, call it by any name. If I am a Hindu, today I have a sacred duty to uphold my dharma. A duty that asks me to try and stop ‘othering’ those who are today the perpetrators of the worst crimes. I have to see that they are as much victims of the human condition as I am. I have to work against my natural inclination for dumping my own insecurity and fear even on them.

On the other hand, I have to insist that as a society we operate from the highest spiritual ideals, “Seeing the Self in all and all in the Self”

One who knows the Self … “regards gold, mud, and stone alike, and is equal before the pleasant and the unpleasant, equal in the face of praise and condemnation, and before honour and insult, and to whom friends and enemies are alike….such a one is said to be above the gunas” ( Ravindra 2017, Shloka 14.22-25). And that is the goal of my sadhana.

Vinita Kaushik Kapur