I have often wondered what J. Krishnamurti meant by “Flowering in Goodness.” The word goodness is so closely tied to what is culturally considered right or better—the proper way to be and act—that it quickly becomes linked to approval and disapproval, again based on cultural definitions of right and wrong.

In conversation with a group of friends, it became clear that goodness is a corollary of perceiving the Unity of all Being. If there is no “other,” there is no need to harm or “other” anything—human, plant, or animal—because all are the same as oneself.

This understanding plays out in daily life in how we relate to those who seem “other than me.” In the Abrahamic traditions, there is a clear injunction to care for the other as oneself. In Christianity, the commandment to “love thy neighbour as thyself” directs us to work toward unity. In Islam, the giving of zakat—sharing one’s good fortune with those less fortunate—reflects the same view of the world we inhabit.

The Hindu understanding of the Unity of Being is lofty in its declaration of the Oneness of all that is. Over time, however, this has sometimes been eroded by an overly ascetic denial of the manifested world as mere maya, or illusion. Giving daan, or charity, is then too often perceived as an act that enhances personal virtue rather than a manifestation of compassion for shared Being.

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff placed great emphasis on putting oneself in another person’s place, even giving exercises to some of his pupils to cultivate this ability.

Consciously and deliberately practicing the act of standing in another’s shoes allows us to see the other as they are. The moment there is an inner movement that sincerely wishes to know the reality of another being, it brings with it a deeper acceptance of what is other than me. As AA. Milne says through Pooh “ Weeds are flowers too, once you get to know them”

In the temporary softening of personal identity, I also free myself from the strictures that keep me imprisoned within it. Such acceptance allows for a flow of ideas—and even sensations—that one might never experience within the cocoon of identification with a limited personality.

Putting oneself in another’s place makes the usual boundaries of body and selfhood more porous, facilitating an exchange of energies between people, plants, animals, and the myriad manifestations of great nature. At times, this can be sensed as a conscious participation of energies between different forms of life—between humans and other species such as dogs, cats, bees, and certain plants.

In the early 20th century, Jagadish Chandra Bose, the renowned Bengali scientist, invented the crescograph to measure plant responses. He is often credited with demonstrating the sensitivity of plants, especially by encouraging his Roses to grow without thorns! Today, research into plant and animal intelligence—using advanced technologies—continues to affirm their participation in a larger field of consciousness.

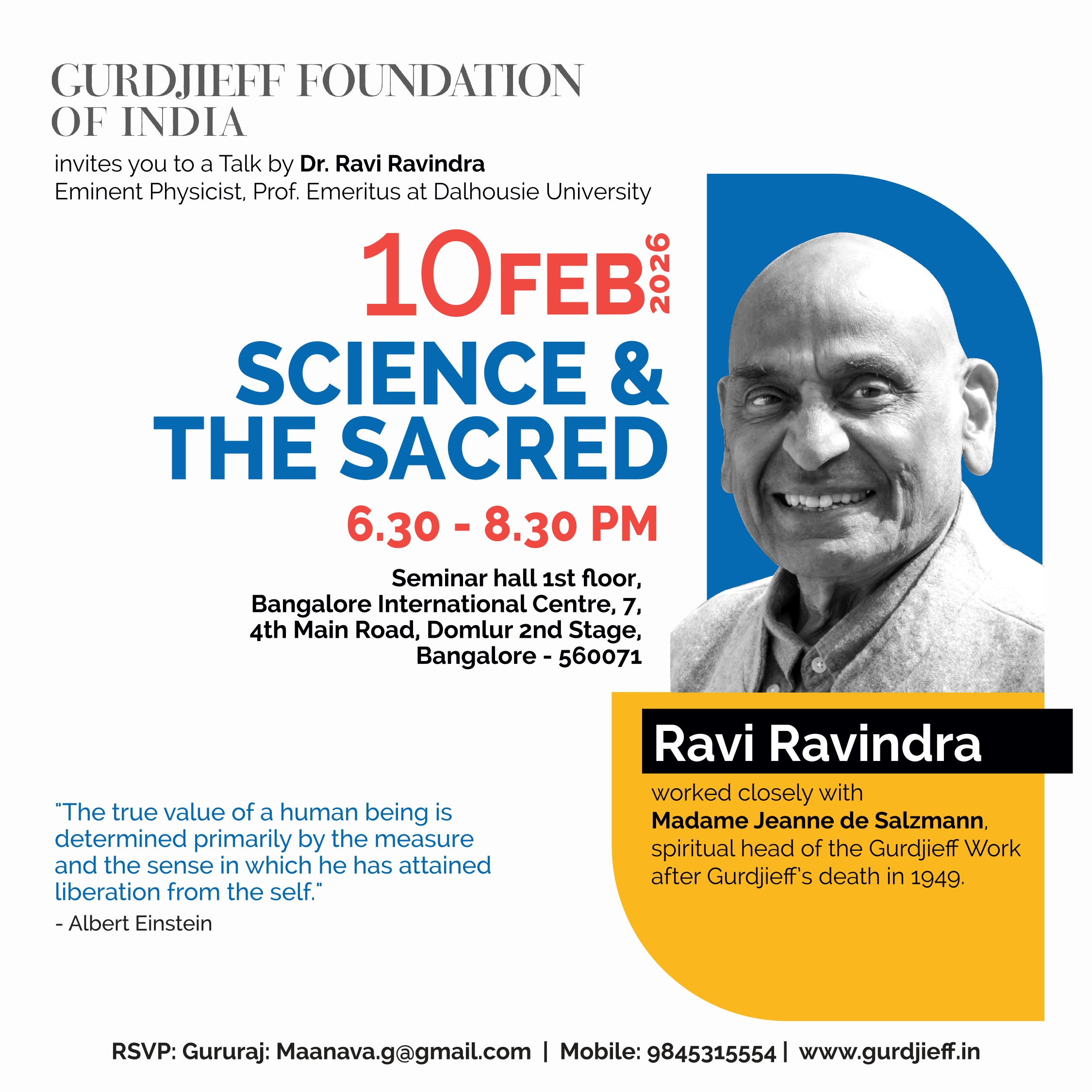

Conscious energy is that which can move between and beyond the boundaries of the body. In small but real ways, we can know how love for another is felt as participation in a common life. Madame Jeanne de Salzmann observed, “The Earth is in need of conscious energies. If some people do not work, the Earth will fall.”

Opening to this statement expands a limited worldview that confines the self to the personal body. A conscious awareness of the Earth encourages actions that foster and nurture the planet, rather than perpetuating the greed and exploitation that arise from objectifying it. It is also a call to emanate conscious energies that can assist the Earth in maintaining its own state of aware existence within the planetary cosmos—an act that implies participation in a scale of manifestation far beyond the grasp and projections of the mind.

The same principle applies to our relationships with people. Objectifying others—defining them by gender, age, or social status—creates separation that runs counter to the truth of the Unity of Being. Once objectified, the reality of the other becomes invisible. Action then springs from the perceiver’s narrow identification, filtered through limiting parameters.

Putting oneself in another’s shoes loosens identification with one’s subjective self-involvement. It allows us to step outside the small definitions imposed by our conditioning, creating the possibility of a more universal perception.

As this unfolds, there is a natural movement away from self-occupation and its corollary, self-importance, bringing us closer to the truth of the One life in all.

By attending to the immediate, genuine needs of the other—whether animal, human, insect, or plant—we begin to participate in the great Oneness, as the personal self-aligns with the Supreme identity of the Self.

Vinita Kaushik Kapur

31st December 2025